Allpa Ruru breaks down the cost of production and earnings of Peruvian smallholders. See next how much they are getting paid and what they need to making a living

Last month, Michael Scherff and Carlos Krapp of Allpa Ruru took us on a journey to Chamchamayo in the Junín region of Central Peru. Not any journey but rather one through bumpy roads on the back of a WWII Jeep leading to the farm of Roberto Boado, Finca La Perla. They guided roasters off the beaten track, showing the conditions in which Peruvian farmers live and work. When it comes to finances, there are more holes in growers’ pockets than on those battered roads.

Peru is a large country where most producers have small plots of land. The history of these farms goes back to the 1970s when the government introduced an agrarian reform and distributed parcels of land to farmers. Back then, they were each given plenty of land to foster a healthy production. But “there is a heritage system in Peru in which fathers will split the farm among their children. At the time they all had seven, eight or nine children,” says Michael. This is why today’s farms are only 3 hectares big on average, thwarting their commercial viability.

This is not to say Peruvian farms are not viable businesses. Improving the yields of coffee plants - currently under 1 tonne of parchment per hectare - can improve their profitability significantly. However, prices are still not where they need to be, even if 2021 has seen market rates rise above US$ 1,60 per pound. During our virtual trip, Michael and Carlos presented a price breakdown of coffee production that shows farmers are currently being paid above costs. However, the sum of their profits from coffee are still below the estimated living wage for the country’s rural areas.

Below are the key facts presented. This is an exercise in costs and profits. There were limiting factors to this calculation as accurate numbers that would be representative of the entire country would require a large research.

.jpg?width=770&name=cost_profits_infographic_2%20(1).jpg)

- Growers usually get their last payments around November. By the time of harvest, many need credit to cover expenses and the costs of production.

- Pickers work from 7 am to 5 pm. They pick around two sacks of 80 kg of cherry per day, which they carry on their backs up to the farm’s processing facility. The cherries are weighed in 14 kg cans. Pickers earn around US$ 1,80 per can (around US$ 20,00 per day). Not all farmers only hire pickers for the season. Many will rely on family labour or will exchange it for work on neighbours’ farms.

- Most farmers will take on other jobs out of the harvest season to cover personal expenses. In Chanchamayo, as crop diversification is limited due to the climate in high altitudes, farmers will work in bars, restaurants, as taxi drivers, etc.

- The two main costs for farmers are fertilizers (three rounds every year at the cost of US$ 750,00 in total per hectare) and picking, which can add up to US$ 620,00 per hectare. Allpa Ruru’s calculations are “conservative”* and focus on the main costs only. Other variable costs such as investment in new plants, new machines, plastic bags for parchment and the farmer labour on the administration side were not calculated.

- The average price to take a 70 kg bag of parchment to the cooperative is US$ 5,40 per sack paid cash at the time of delivery. Producers usually drive their coffees to local warehouses once a week. If they don’t have a car they need to wait until a neighbour is driving down.

- Based on Allpa Ruru’s calculations for an average farm, the farm gate price of a coffee needs to be a minimum of US$ 3,00 per kg to give a farmer and his family an “income to live from” and comparable to the basic income in other parts of the country (this excludes other potential sources of income).

- To calculate the “minimum price”, Allpa Ruru took the basic income in Lima (US$ 324,00 per month), where the company is based, as a baseline. A farm gate of US$ 3,00 per kg would translate as roughly US$ 313,00 per month.

- The current farmgate price is at US$ 2,56 per kilo (price at the end of May).

- Based on a farm gate of US$ 3,00 per kg, the minimum FOB price would be approximately US$ 4,95 per kilo (based on a container being shipped full). Please note that these will vary according to the volume that is being shipped, the distance between the warehouse and the port etc. Details need to be discussed on a case by case basis with producers and exporters.

- Access to credit is one of the main obstacles for small farmers. Banks won’t always provide finance as not all farmers have the deeds of their land and, as these are considered to be high-risk loans, the interest rates can be as high as 30% in a year. An interest rate of 10% in a year could represent an income increase of more than 50%.

- Local intermediaries can buy the farmers’ coffees cash in hand to help with cash flow. However, they pay below market price. They also provide loans at abusive rates such as 10% a month.

- Small farmers love knowing what happens to their coffee after it’s sold and feel proud to export. However, as payment for exports are slower, they would benefit from fast decision-making from buyers (it helps them to secure credit with exporters and coops) and, ultimately, for long-term relationships which can offer farmers good stable prices.

Right now, prices for green coffee in Peru are far from being fair, even when they are above the C-market and based on Fairtrade premiums. They are at subsistence levels. Currently, international viewers (such as this and this) calculate the basic living income in Peru at around US$ 610,00 per month. Reaching a living income depends on more than price. It encompasses access to land, access to credit, crop diversification and an increase in yields.

Ironically, now that market prices went up, producers are being pushed to offer cheaper coffee because buyers expect prices to be kept at the same rate as they have been before. Small producers need prices to go up to get a chance to scale their operations to become more cost-effective. If buyers are only looking at the market and judging prices against Brazilian coffees, small growers in other countries will never get to take a breather.

*All price estimates are approximate. They were provided by Allpa Ruru for illustration purposes only.

***

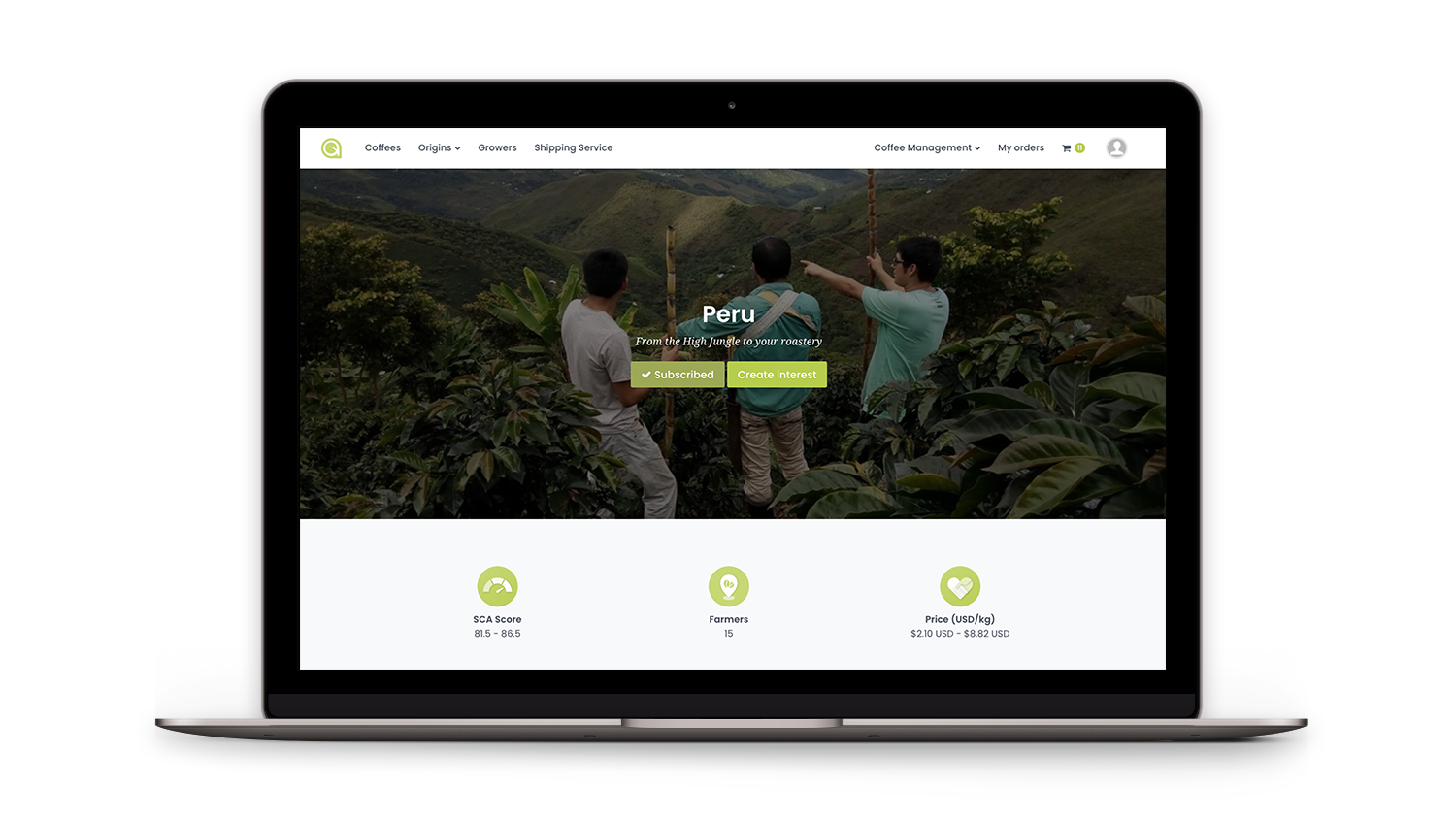

Learn more about Peru, meet growers and browse coffees in the Algrano platform.

Let Us Know What You Thought about this Post.

Put your Comment Below.