In this article:

- What's FOB?

- Why do you see the FOB but not the farm gate price?

- Can the FOB price be used as an indicator of how much farmers get paid?

- Farm gate to FOB ratio: examples from Ghana, Brazil, and Costa Rica

- Other factors that influence farm gate prices: currency conversion and interest rates

- What questions should buyers be asking about price?

What is FOB?

FOB stands for Free on Board. It’s an incoterm (international commercial term) used in export-import trade contracts and the standard in the coffee industry. It’s also the first price you see when looking for coffees on Algrano.

The incoterm serves as a benchmark for price comparison because it’s adopted in most green coffee contracts, including in the futures market and Fairtrade sales. Being able to compare your price acts as a sort of compass, even if it’s an imperfect one.

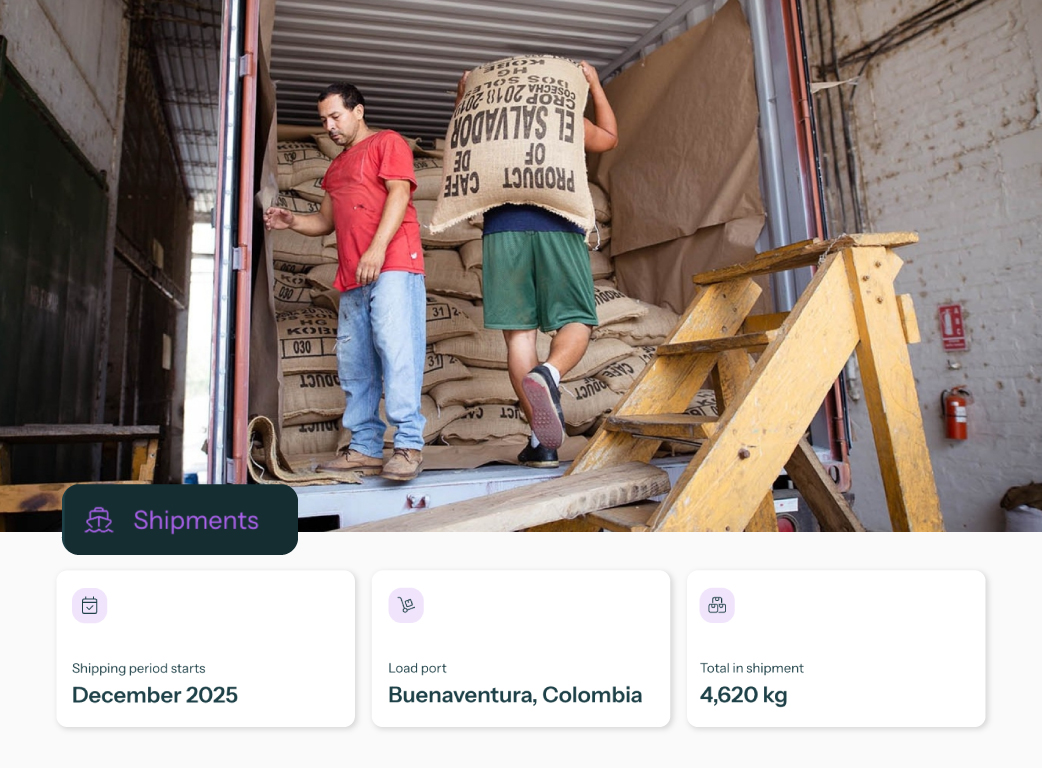

More than price, the incoterm defines when the seller is paid and where the buyer takes over responsibility and risk. In the case of FOB, sellers are paid when the container is shipped and responsibility changes hands at the port of departure.

The coffee industry has become more transparent over the past decade and FOB prices have become more visible. The assumption here is that they give buyers assurance that producers are getting fair prices. But how does it work?

Here’s the thing. In coffee, the farm gate price is only one component of FOB. Many other fees are built into the cost of green to reach an exportable price. Here are some of them:

- Processing costs (at wet or dry mills)

- Sorting for defects and size screening at dry mills

- Packaging (Grainpro or similar, jute bags, and bag marks)

- Domestic transportation to a warehouse and later to the port

- Handling of the bags at the warehouse and port (loading and unloading)

- Exporting documentation, usually handled by a customs broker

- Taxes charged by each country for exporting

For the sake of simplicity, let’s summarise this complexity in a simple formula:

FOB price = farm gate price + exporting costs + taxes

Why do you see the FOB but not farm gate?

Farm gate refers to a domestic price. It doesn’t appear in international contracts because it’s not an incoterm. So the easiest way to know the farm gate is to ask a producer after purchasing coffee. On Algrano, you can reach out to sellers at any point in the buying process. So why ask after the order? Well, because providing farm gate prices is not as simple as it may look.

Two types of sellers can easily provide farm gate information:

- Single farms that sell only their own coffee

- Wet mills in countries like Ethiopia and Rwanda, where the government regulates or indicates cherry prices. There are considerations though, and the farm gate will be approximate.

Your supply chain can be very different to these two cases though.

The picture is more complex when a cooperative or exporter buys coffee daily over time paying local market rates. These are influenced by the futures price and change every day. So one lot can be created out of coffees with different farm gate prices.

Smaller cooperatives might only buy coffee after a contract is signed because of cash flow. Others have a two-payment structure, where a second payment is made after the harvest, averaging all contract prices.

While it’s possible to access the farm gate price for every purchase on Algrano, producers sell coffee to roasters in the same way as they do to importers and get paid once the coffee is shipped. Algrano doesn’t set the FOB prices - producers do - and none of the coffees on the marketplace have been bought yet. That’s why the first price roasters see is the FOB.

Can the FOB be used as an indicator of the farm gate price?

It’s not wrong to assume a higher FOB means a greater farm gate price. But it’s not always right either. Milling and exporting costs vary widely between countries and regions and there’s a lack of industry-wide data.

The composition of farm gate also varies. The more autonomous producers are (i.e. having their own processing facilities, dry milling, sorting machines, etc.), the more they can deliver coffee closer to exportable grade, fetching a higher proportion of the FOB.

Despite the different supply chain configurations and the variations they bring to the farm gate to FOB ratio, Free on Board prices can still be used as pointers on how much producers get paid as long as you understand how your suppliers are structured.

Farm gate to FOB ratio: examples

Now that you understand better what FOB prices are, we’ll look into a few real market examples. In this section, you’ll see what the farm gate to FOB ratio looks like for different types of suppliers in different countries.

Buying parchment in Ghana: 75% farm gate + 25% export costs

Farmers sell coffee cherries in many African countries, such as Rwanda and Ethiopia. But in Ghana, they typically sell parchment (when the dry beans are still covered by a protective layer).

“It is the exporter's responsibility to de-hull the coffee, sort the beans, and get them ready for exportation,” says Emi-beth Aku Quantson, CEO and founder of Kawa Moka, Ghana’s largest specialty coffee roastery.

In July 2022, Emi-beth shared that the average farm gate price paid to producers for 65kg of robusta in parchment is 350 Ghanaian cedi (≅US$ 42.00). For one bag of exportable green coffee, Emi-beth needs two bags of parchment as 20% is removed (foreign matter, defects, screen size).

Kawa Moka pays above average. They spend 1,000 cedis (≅US$ 120.00) to get one 60kg bag of exportable green. This includes 30-50 cedis (≅US$3.60 - US$6.00) for picking and 60 cedis (≅US$7.25) for transport.

Their FOB price composition is: 75% farm gate (processed up to parchment at the farm) + 15% transport + 5% documents (inspection, certification, sealing, etc.) + a 5% exporter fee.

“Five per cent for the exporter is not always possible as it all depends on the final price paid by buyers. Robusta from West Africa is always a hard bargain,” she adds.

Buying bica corrida in Brazil: 85% farm gate + 15% export costs

In Brazil, “the most common path would be the farm, even smallholders, processing the coffee until what we call the bica corrida stage [unsorted green beans],” shares Allan Botrel of Sancoffee, a cooperative in Minas Gerais.

“All post-harvest, wet milling and even initial hulling take place at the farm, and that coffee is traded in green [rather than cherries or parchment] in domestic markets, with prices expressed in local currency [BRL or Brazilian Real] per 60kg bags,” he explains.

As a result, FOB prices in Brazil have a higher farm gate to FOB ratio than in Ghana. Allan estimates that roughly 85% of the Free on Board is farm gate. Then 10% are logistics and 5% is the exporter’s service margin. This can also change depending on the buyer’s chosen grade and market conditions.

Buying milled and sorted coffee in Costa Rica: 88% farm gate + 12% export costs

Compared to Ghana and Brazil, the farm gate to FOB ratio in Costa Rica is higher because producers go a step further in the supply chain by sorting their beans.

In Costa Rica, green coffee is sold in rieles. This is the price for milled and export-ready green coffee per quintal (46kg). Originally in Costa Rican colóns, the rieles price is later converted to American dollars per pound.

Normally, producers (or mills) are responsible for the coffee until hulling and sorting. In many cases, mills pay for packaging and transport to the exporters’ warehouse where bags are loaded onto containers. The rieles price covers all costs until the warehouse.

For the 2021-22 harvest in Costa Rica, the average farm gate (rieles) to FOB ratio of Bean Voyage, a feminist organisation that supports smallholders with training and market access, was 88% to 12%. Export costs added up to 10.5%, including paperwork and the exporter margin, and 1.5% went to mandatory ICAFE (Coffee Institute of Costa Rica) taxes.

Other factors that affect the farm gate

Currency conversion

Though FOB prices are set in American dollars per pound (Arabica) or per metric ton (Robusta), domestic trade happens in local currency. Why does it matter?

If a farmer is paid after exporting, buyers will only get accurate farm gate figures after the exchange rate is fixed. If the coffee had already been bought locally by a coop or exporter, their margins would be affected by currency fluctuations.

Standard specialty lots scoring from 80 to 83 points are more exposed to currency risk than micro-lots. They are usually priced on differentials, hovering above the futures price. As margins are thin, sellers normally expect to make gains on the exchange rate but that’s not always possible.

Interest rates

Most producers and organisations carry the burden to pre-finance the harvest, paying for coffee and workers. And producing countries tend to have higher interest rates than Europe or the USA. That affects how much of the farm gate is eaten by costs.

Direct trade farmers that export their coffee wait at least three months between harvest and payment. At this time, interest is being accrued. Time is money, the longer producers wait for buyers to cup and order, the more they accrue costs.

More often than not, farmers who sell directly also sell part of their crop locally to cover operational costs faster. This is illustrated by smallholder Ana Rosa Marañon in Veracruz, Mexico.

“My family and I collect coffee cherries six days a week during the harvest. From Monday to Friday, we bring home the cherries we harvested to process and sell as parchment. For the harvest on Saturday, however, we sell cherries to get cash on the spot and pay for the following week’s picking.”

In 2023, Algrano launched a pre-payment pilot for coffee producers on the marketplace to reduce their waiting time. Through the Grower Capital initiative, we offer advanced payment to sellers once a contract is signed with a buyer. Click here for more information.

What should buyers be asking about price?

This is a lot to take in. We get it. The coffee supply chain is a maze of variables and the examples above illustrate only a few specific cases.

Given the different supply chains, payment timelines and interest rates, it’s important to ask your coffee suppliers the following questions to understand the impact of your sourcing choices:

- Who exports your coffee?

- For cooperatives, when is your coffee bought from the producer?

- How are producers paid? What are the payment terms and timings?

- Are producers being pre-financed? What’s the interest rate?

- How are risks spread across the supply chain?

While not being able to put a number on fair prices is frustrating for buyers, direct trade creates the opportunity they need to assess their sourcing practices. This is the foundation of a solid sourcing strategy with real impact.

.png)